Raising the bar? A Case Study on Evidence and Perceptions Relating to Rat Cage Height in the UK

Raising the bar? A Case Study on Evidence and Perceptions Relating to Rat Cage Height in the UK

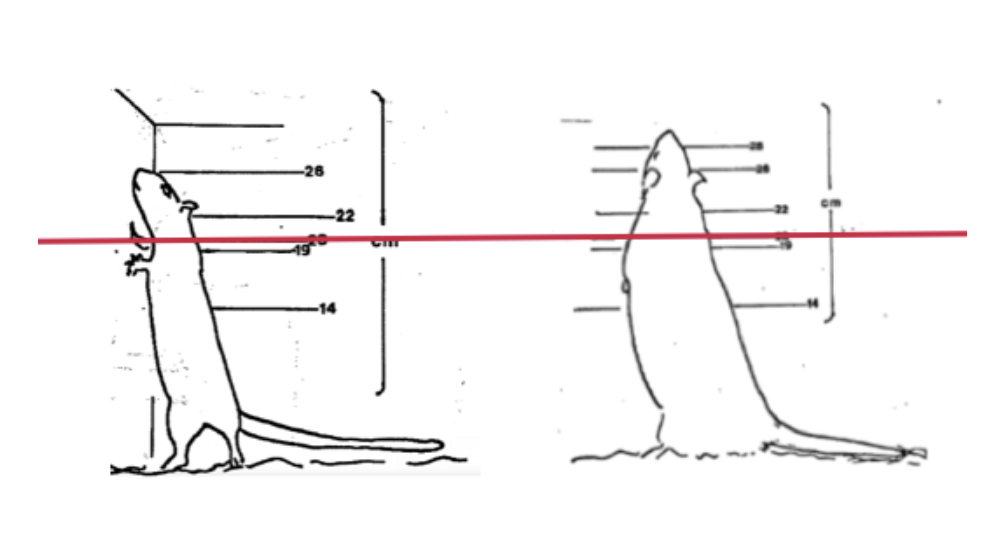

Over 175,000 rats are used in research and testing in the UK every year, with millions more used worldwide. Many of these are housed in cages that do not allow them to stand upright as adults. For example, the current Code of Practice to the UK 1986 Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act stipulates a minimum height of 20cm, but adult rats can rear to 30cm (see above). There is evidence that standing upright is important for rat welfare and not being able to do so could lead to increased lateral stretching and discomfort[i], but many rats are still housed in cages that don’t allow this.

We wanted to find out why, for two reasons: First, we were motivated by the animal welfare and ethical issues – why does it appear to be acceptable for rats to be restricted in this way when other animals are not? Second, we were interested in the beliefs of people with different roles in animal research facilities (vets, animal caretakers, researchers, managers) regarding the body of evidence that is required before they will change to higher cages.

Some designated establishments recognise that housing rats so that they cannot stand up is a welfare (and scientific) issue and have already moved to higher cages, whilst others have not. We visited eight different establishments, with a mixture of rat cage types, interviewing key members of staff to identify the main barriers and solutions to adopting higher cages. The results of this study were written up in an article[ii] as part of the Special Issue in the journal Animals celebrating ‘60 Years of the Three Rs and Their Impact on Animal Welfare’.

We found that the main factors hindering the implementation of higher caging could be classified into five different groups; health and safety, financial considerations, animal welfare, scientific factors, and human perceptions. For instance, there was the health and safety concern that as higher cages require taller racks, lifting cages from the top and bottom shelves could present risks of manual handling injuries. Facilities used strategies to mitigate these risks such as avoiding the top and bottom racks, removing water bottles before lifting, and limiting group sizes to two to four rats per cage. Financial and space constraints were also often cited, more acutely in some facilities than in others. However, the rhetoric advocated was that if the animal welfare benefit was sufficiently significant and evident, finances would not be a barrier.

A repeated scientific concern related to effects on the data, such as the worry that the baseline for studies could be shifted and might need to be re-established. Some researchers saw this as negative, consuming time and resources. One researcher, however, saw re-validation as a valuable part of progress, a “short-term cost for a long-term gain.” Another highlighted the inevitability of re-validation, pointing out that sometimes this had to occur if manufacturers reformulated feed or bedding. The refrain of ‘better science, better welfare’ was repeated throughout all the facilities, most asserting that more translatable and repeatable data could be obtained from more naturally behaving animals.

Certain human perceptions presented barriers to implementing refinements. Some interviewees were sceptical about the significance of rearing in rats’ behavioural repertoire, despite the evidence of its importance.Moreover, many respondents were cautious not to appear to conflate the needs of humans and those of animals. There was a conscious effort to identify and problematise anthropomorphism if it ever arose. Although some participants appeared to be getting ‘stuck’ on the concept of anthropomorphism, others recognised that critical anthropomorphism can be useful in identifying refinements to evaluate. In other words, thinking “if I were a rat, I’d like that” can in fact be a useful starting point, provided that this assumption is then critically and empirically evaluated, using recognised animal welfare science techniques.

We were also interested in the process of successfully enacting animal welfare changes. It was especially noteworthy that ‘hard’ scientific evidence was required to change practice, whilst anecdotal evidence was often accepted to justify not making changes. Moreover, when asked what kind of evidence would convince them to change practice, many respondents described evidence that was already available, such as physiological data on bone density and muscle growth. This indicates a pressing need to raise awareness of such studies. We included a table that compared desired evidence and existing evidence in our paper to illustrate this.

In the facilities that had made the most progress in implementing refinement, this was often driven forward by one or several charismatic individuals. Animal technologists were often very progressive in pushing for change, although at other times they were cited as opposing change. We were very encouraged to see the respect and value afforded to the experience and opinions of animal technologists, who as a body are a critically important resource with respect to improving animal welfare and the quality of the science.

To sum up the most salient points from the article, it is important to be cautious of inconsistency in how evidence is valued and evaluated. This was observed in the cognitive dissonance of those respondents who required hard science to back up the need for a refinement on the one hand, yet accepted (and created) anecdotes that justified the status quo on the other. In addition, clear knowledge gaps were identified in animal behaviour and welfare needs, coupled with a lack of awareness about animal welfare science, so it would be worth considering ways of making training on behaviour and welfare more impactful.

We hope that this test case will lead to further discussions regarding the level and nature of evidence required to improve animal housing, husbandry and care; when it is appropriate to change mandatory Codes of Practice, and how to ensure that all staff receive adequate training in animal behaviour and welfare science.

Author Biographies:

Hibba Mazhary is a part-time PhD student at the School of Geography and the Environment, University of Oxford. With a background in human geography and environmental studies, her PhD focuses on farm animal welfare but she has also recently been working on a project with the RSPCA on laboratory animal welfare.

Penny Hawkins is head of the RSPCA Research Animals Department in 1996, which works to implement the 3Rs and ensure robust ethical review of animal use. Key initiatives include improving lab animal welfare and reducing suffering; working with the scientific community to end ‘severe’ suffering; and providing education and training for all those involved in animal use worldwide. Penny’s work mainly relates to refinement and supporting and promoting the work of Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Bodies (AWERBs).

_________________________

[i] Makowska, I.J.; Weary, D.M. The importance of burrowing, climbing and standing upright for laboratory rats. R Soc. Open Sci 2016, 3, 160136. Available online: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsos.160136 (accessed on 14 November 2019).

[ii] Mazhary, H.; Hawkins, P. Applying the 3Rs: A Case Study on Evidence and Perceptions Relating to Rat Cage Height in the UK. Animals 2019, 9, 1104.